Leveling Up: phpspec, TDD and Mock Objects

- Composer

- PHPSpec

In this edition of Leveling Up, we’ll continue where we left off last time, using phpspec to develop code using a TDD (Test Driven Development) workflow. Last month, we got started with some very simple specs creating a very simple single function calculator with no dependencies. However, most of the code you’re likely to build will be quite a bit more complex. This month, we’ll talk about how phpspec can help you build code that relies on other objects to do the work, even if that code doesn’t even exist yet.

Introduction

Very early in your OOP in PHP career, you may have build methods that created other objects in order to utilize some functionality those objects provided. Perhaps you later organized the places that created these new objects into “getters” since you might have needed these objects in more than one place, and code duplication is bad, mmmkay? If you have code like this, and you’ve tried to write unit tests against this code, you probably discovered that it’s rather difficult to test code in isolation that creates other objects.

Each object that we use within another object is a dependency we must contend with now. When the objects we want to test create other objects themselves though, this is a problem. We must test these objects that may provide, or cause, real side-effects. Imagine code that we want to test for the deletion of records in a database, and imagine the object itself creates the database connection within itself. In this case, we can only test the code by creating real records and really deleting them. The same holds for other dependencies, especially ones that tie into the file system, databases, and APIs (including APIs that charge per usage). Hard-coded dependencies lead to difficulty testing code and may lead to real charges.

Good thing there’s a solution to all of this. It’s called dependency injection. In case you’ve not heard of it, dependency injection is essentially passing in objects as parameters. Rather than building objects that know how to build their dependencies, they simply allow the dependencies to be passed in to methods in the object which then uses them. If an object requires another object in order to be functional, it’s often a good idea to require this object as a constructor parameter. That way the object can be assured the dependency exists. Other forms of dependency injection include setter injection. This is setting a dependency into an object after the object has been created. Additionally, if a single method needs an object to complete its work, you can send the object into only that function.

Single Responsibility Principle

Objects that are well designed should follow what’s known as the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP). It’s the “S” in SOLID, which will be the topic for a future article. SRP means that each object should have a responsibility of doing only one thing (and doing that one thing well). If your object has something to accomplish other than knowing how to build and configure its dependencies, then it’s probably doing too much. That being said, there are objects that can build other objects. That’s pretty much the definition of the factory object, but right now we’re not talking about factory objects.

Testing, or writing specs for objects, is best done when those objects have injected dependencies, and when we follow what’s known as the Law of Demeter. The Law of Demeter is also known as the principle of least knowledge and says the following:

* Each unit should have only limited knowledge about other units: and then only units "closely" related to the current unit

* Each unit should only talk to its friends; don't talk to strangers

* Only talk to your immediate friends.

Another way to state this is that we tell a dog to walk, we don’t tell the dog’s legs to walk. Now the dog’s internal system and structure tell its legs to walk, but we don’t have any knowledge of the internal structure of the dog, or how it goes about telling the legs the message to start walking. But enough theoretical code, principles, laws and what-not. We need to start building some spec and some code.

Diving Back into Phpspec

Let’s assume you’ve got phpspec installed from last time. If not, composer require phpspec/phpspec, should set you on the right path. I’m going to also assume that you’ve placed vendor/bin/phpspec of your directory in your PATH environment variable, so from here forward, when we want to run phpspec it will be just phpspec instead of vendor/bin/phpspec. Let’s also take a look at what we’re going to be building. We’re going to create a class that we can use to tell us if a user is authenticated.

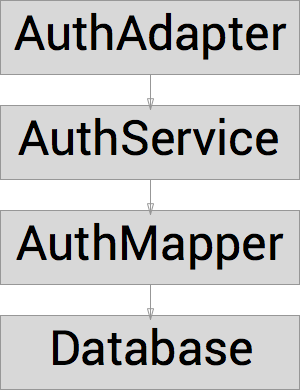

At this point, we’ll assume that none of these classes exist, or perhaps the class labeled “Database” exists, but we won’t be getting that far for it to matter. The important part is that we’ll be building “AuthAdapter” which depends on “AuthService”, which in turn depends on “AuthMapper”, which uses some sort of database.

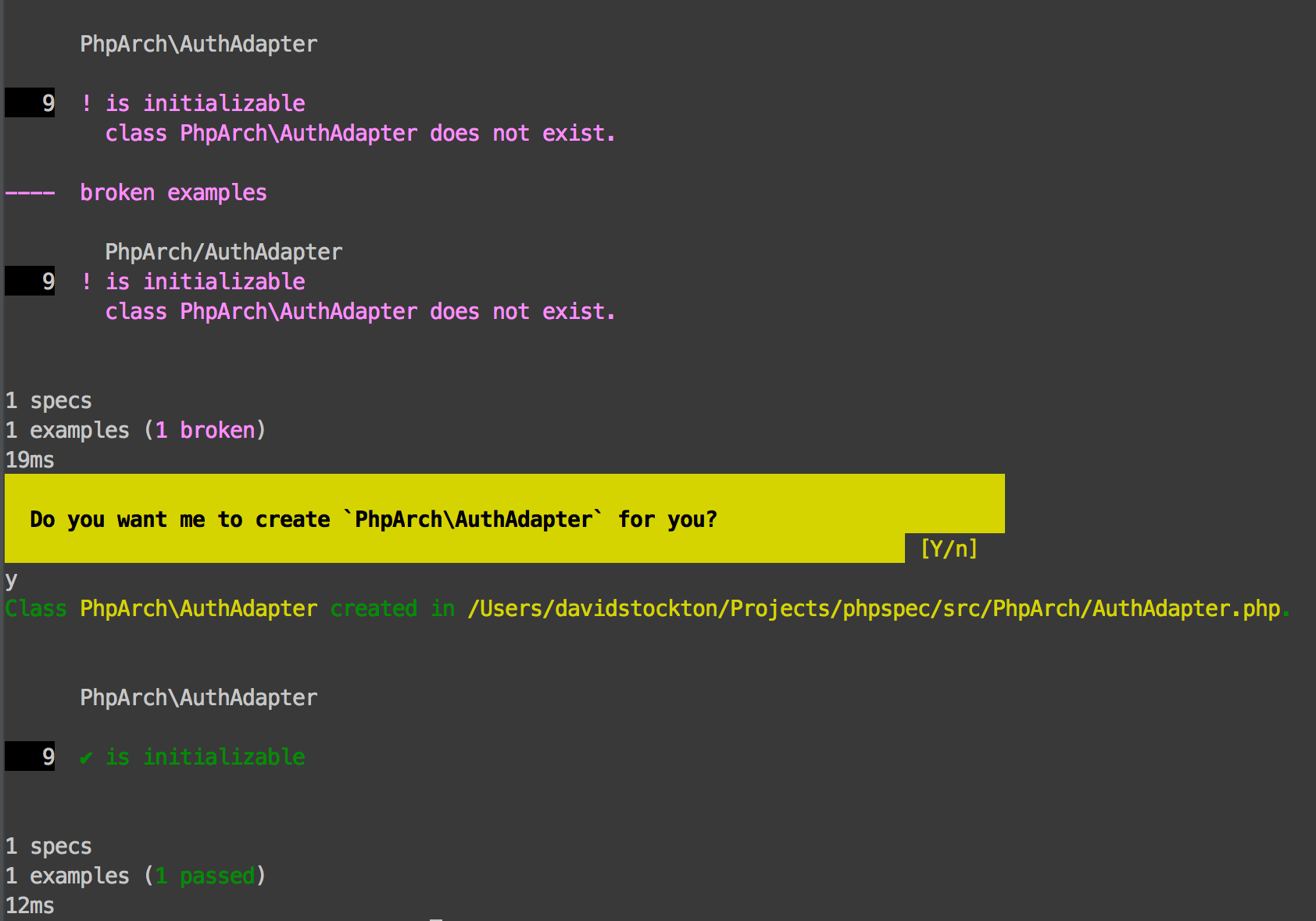

Virtually all classes we’ll be testing/creating using phpspec will start off with the phpspec desc command. So let’s do that now: phpspec desc "PhpArch\AuthAdapter". This will create a spec skeleton in the spec directory called spec/PhpArch/AuthAdapterSpec.php. Inside this class, you’ll find a single method called it_is_initializable, which is a simple test/spec that essentially says that the PhpArch\AuthAdapter class should exist. When we run the specs we’ve created, phpspec will see that the spec fails because that class doesn’t exist. Phpspec offers to create it for us. See figure 2 for what this looks like.

Everything you see in the screenshot should be fairly easy to follow. The spec runs and fails, and phpspec indicates this failure as a broken spec. This is different than a failing spec since a broken spec indicates that there may be a missing class or method, whereas a failing spec indicates that behavior is not what was described in the spec. In this case, phpspec offers to create the missing class, I accepted and it reran the spec which is now passing. You’ll find that phpspec has created an empty class in the standard src/PhpArch/AuthAdapter.php location. The location of source, spec and more is configurable if you wish to customize it.

Simple Beginnings

Let’s add a few more specs that we’ll need in order to make our AuthAdapter work. Of course we’ll need a way to send in a username and a password. These are simple and require no dependencies, so I’ll go ahead and add them both at once. In standard TDD practice, you’d add one of these spec methods, then the code to make it work, then the other, and so on. Listing 1 shows the result of approximately four rounds of TDD, and a little bit of anticipation of what we’ll need next. Let’s take a look.

Listing 1 - Spec for setUsername and setPassword

<?php

namespace spec\PhpArch;

use PhpSpec\ObjectBehavior;

use Prophecy\Argument;

class AuthAdapterSpec extends ObjectBehavior

{

function it_is_initializable()

{

$this->shouldHaveType('PhpArch\AuthAdapter');

}

function it_will_accept_a_username()

{

$this->setUsername('bob');

$this->getUsername()->shouldBe('bob');

$this->setUsername('frank');

$this->getUsername()->shouldBe('frank');

}

function it_will_accept_a_password()

{

$password = uniqid();

$this->setPassword($password);

$this->getPassword()->shouldBe($password);

}

}

You might be wondering what each of these specs are doing. Let’s look at it_will_accept_a_username first. Essentially, we’re telling phpspec that if we were to call a setUsername method with an argument of ‘Bob’, if we call getUsername() then it should return ‘Bob’. Under normal TDD, this would be the first step, and we’d implement the code. However, with normal TDD, the simplest thing that could work to make the test pass would be that a setUsername method existed and a getUsername method simply returned the word ‘Bob’. Since this isn’t enough, I’ve added another call to the setter and getter with another username pair. This should be enough to ensure that the getter and setter actually do what we want them to do.

But, why is it_will_accept_a_password so different then? Well, I’m showing an alternate method of ensuring that the approach of just returning a set string won’t work. The uniqid function in PHP will return a random string of numbers and letters. By sending in this random string, the developer of the AuthAdapter class could not predict the value we’re sending in, so the proper implementation is required. Let’s see what happens when we run the spec.

Listing 2 - Running spec for the getters and setters

PhpArch\AuthAdapter

9 ✔ is initializable

14 ! will accept a username

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setUsername not found.

MacBookPro:phpspec davidstockton$ phpspec run

PhpArch\AuthAdapter

9 ✔ is initializable

14 ! will accept a username

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setUsername not found.

23 ! will accept a password

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setPassword not found.

---- broken examples

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

14 ! will accept a username

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setUsername not found.

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

23 ! will accept a password

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setPassword not found.

1 specs

3 examples (1 passed, 2 broken)

10ms

Do you want me to create `PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setUsername()` for you?

[Y/n]

y

Method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setUsername() has been created.

Do you want me to create `PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setPassword()` for you?

[Y/n]

y

Method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::setPassword() has been created.

PhpArch\AuthAdapter

9 ✔ is initializable

14 ! will accept a username

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getUsername not found.

23 ! will accept a password

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getPassword not found.

---- broken examples

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

14 ! will accept a username

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getUsername not found.

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

23 ! will accept a password

method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getPassword not found.

1 specs

3 examples (1 passed, 2 broken)

12ms

Do you want me to create `PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getUsername()` for you?

[Y/n]

y

Method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getUsername() has been created.

Do you want me to create `PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getPassword()` for you?

[Y/n]

y

Method PhpArch\AuthAdapter::getPassword() has been created.

PhpArch\AuthAdapter

9 ✔ is initializable

14 ✘ will accept a username

expected "bob", but got null.

23 ✘ will accept a password

expected "550fb980b20a9", but got null.

---- failed examples

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

14 ✘ will accept a username

expected "bob", but got null.

PhpArch/AuthAdapter

23 ✘ will accept a password

expected "550fb980b20a9", but got null.

1 specs

3 examples (1 passed, 2 failed)

14ms

Unless you’ve tried something different than I showed, phpspec will have prompted you to create four missing methods and you’ll end up with a final tally of 1 passing spec and 2 failed specs. This is where we get to do a little more coding and add two standard class properties with accessors (getters) and mutators (setters). Let’s do that now.

Listing 3 - Getters and Setters for AuthAdapter class

<?php

namespace spec\PhpArch;

use PhpSpec\ObjectBehavior;

use Prophecy\Argument;

class AuthAdapterSpec extends ObjectBehavior

{

function it_is_initializable()

{

$this->shouldHaveType('PhpArch\AuthAdapter');

}

function it_will_accept_a_username()

{

$this->setUsername('bob');

$this->getUsername()->shouldBe('bob');

$this->setUsername('frank');

$this->getUsername()->shouldBe('frank');

}

function it_will_accept_a_password()

{

$password = uniqid();

$this->setPassword($password);

$this->getPassword()->shouldBe($password);

}

}

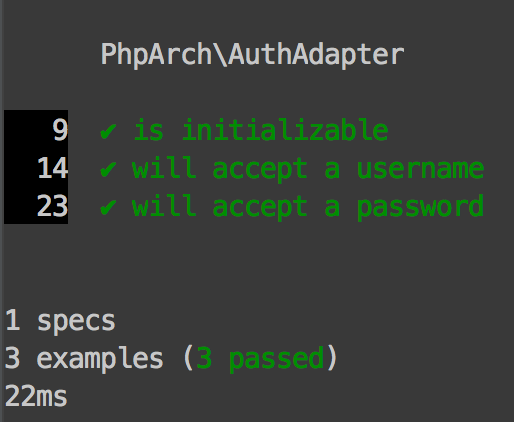

Now if you run phpspec run again, you should see three passing specs. See figure 3. With the simple stuff out of the way, let’s get into the meat of mocks and the power that building with dependency injection brings.

Mocking Objects

Compared to what we’ve seen so far, mocking out dependencies can be a little strange. As I mentioned earlier, we don’t have anything concrete (or even abstract) to inject into our AuthAdapter class. And I’d rather not build anything just yet either. But we need to be able to tell phpspec to inject something useful so that our AuthAdapter class can work, at least in our testing scenario.

We can accomplish this by using interfaces and type hints. First, we’ll build an interface for what we’re anticipating the AuthAdapter will need from the AuthService. In otherwords, we’ll build an interface for the AuthService and then use the interface in our spec. I’m not sure if there’s a more TDD approach to building the interfaces, but since there’s no actual code, I think it will be ok. If you know of a way to be more “TDD” and create interfaces using the standard TDD approach, I would love to hear about it. Listing 4 shows the interface we need for now.

Listing 4 - Interface for AuthService

<?php

namespace PhpArch;

interface AuthServiceInterface

{

/**

* Returns a user object from the provided username. Provides

* AuthUser if username was found or a GuestUser if not found. It's

* the caller's responsibility to check credentials if needed.

*

* @return UserInterface

*/

public function getUserByUsername($username);

}

Over the course of the remainder of this article, you’ll likely see references to various classes and interfaces, none of which currently exist and none of which will be by the time you reach the end. However, I’d encourage you to try out the TDD workflow with phpspec and create the other classes. If you look at listing 4, you’ll see I’ve defined a single method in the interface. The purpose of the interface is to retrieve a user object, which we can imply will conform to a not-yet-created UserInterface interface. Additionally, we know of two (also non-existent) concrete implemenations of the UserInterace – the AuthedUser and the Guest User. On your own, you could create the interface and then describe and create the two implementations. We won’t need them right now.

Finally, it’s time to build some spec that requires other classes that don’t exist. Phpsepc uses type hints to help determine what is required in our classes. Additionally, it has a special method called let which like PHPUnit’s setup method, is run before each of our tests. Since our AuthAdapter class will not be of any use without an AuthService, I’ve decided we should be injecting it into AuthAdapter via the constructor. We’ll do this by adding the let method and a new call, beConstructedWith. Add this method at the top of your AuthAdapterSpec.php code:

function let(AuthServiceInterface $service)

{

$this->beConstructedWith($service);

}

Calling phpspec run now prompts you to create a __construct method on our AuthAdapter. If you allow it to create it, it will build a constructor skeleton that takes a single parameter and contains no body. It will then re-run the spec and we’ll see there are still three passing specs. Phpspec uses type hinting to build fake versions of our objects, in this case, a fake object that implements AuthServiceInterface. Adding the constructor didn’t really change anything with how the code ran. We could test that the constructor parameter was actually used to set some property, but that seems like we’re getting too much into the implementation at that point. Instead, we’ll see to it that the constructor does what it needs to do through the addition of other spec.

Other tests we’ll need to implement would include a test that ensures that if the user doesn’t exist, we’ll return a GuestUser. If the user does exist but the password doesn’t match, we’ll also return a GuestUser. And finally, if the user does exist and the password matches, we’ll provide an AuthedUser.

Greater Expectations

Creating the first test is straight forward, and it starts to show the true power of mock objects. Imagine building a test without using dependency injection. In order to test the first scenario, that a user that doesn’t exist should return a GuestUser, we’d need to have a database set up and then search on a user that we are pretty sure doesn’t exist. If that user ever did exist, our test may fail. Mocks allow us to make up whatever scenarios we want our code to handle, from the user not existing, to the database connection going away, or disks running out of space, API endpoints being down, etc. All of those scenarios would be difficult to test for and even more difficult in an automated fashion. We certainly don’t want our tests to actually bring down the database or disconnect the network.

On to the spec. In the code below (added to our AuthService spec), you’ll see that we’re now passing in and using a variable called $service. This variable matches the name of the AuthService variable we sent in through the let method. In fact, it’s the exact object. We can now provide some fake functionality to our service and see how our AuthAdapter should deal with it. We’re first telling the $service that if getUsername is called with a string of ‘bob’ it should return some other parameter we’ve passed into the spec, called $guestUser. Additionally, the type hinting indicates that $guestUser should be a mock of the \PhpArch\GuestUser class (technically a dummy since it has no functionality). When we call authenticate, we should get back an instance of GuestUser. (In the code below, I’ve added the appropriate use directives, so I don’t have the full namespace).

function it_will_return_a_guest_if_user_not_found($service, GuestUser $guestUser)

{

$service->getUserByUsername('bob')->willReturn($guestUser);

$this->setUsername('bob');

$this->setPassword('nomatter');

$this->authenticate()->shouldHaveType(GuestUser::class);

}

Now if you run the spec again with phpspec run, we’ve got one broken spec since the class doesn’t exist. The easiest way to fix this is to describe it and let phpspec build an empty class for us.

phpspec desc "PhpArch\GuestUser"

phpspec run

That should be sufficient to make phpspec stop complaining. Now it will prompt you and ask if you’d like it to create the authenticate method on our AuthAdapter for us. Since it’s just skeleton code, why not? It will then re-run automatically and we’ve got a single failing test. The test that failed says that it was expecting a GuestUser but instead got a null. The simplest thing that could work would be to have our AuthAdapter’s authenticate method return a new GuestUser. Afterwards, all our spec should be passing again.

public function authenticate()

{

return new \PhpArch\GuestUser();

}

Super! Except now we’ve got a perfectly good AuthAdapter that only works correctly for people who try to authenticate and don’t actually have a user account. In order to fix this, we need to add more spec which will give us the ability to add or change code. Let’s build a spec that ensures our adapter will give us an authenticated user if the user exists and the password matches. Since we need to have the AuthedUser, let’s go ahead and describe and create an empty one for now:

phpspec desc "PhpArch\AuthedUser"

phpspec run

We’ll confirm that we want it to generate the AuthedUser class. Now we need to set up a spec to ensure logging in will work correctly. Listing 5 shows one way we could build this spec. This function will go into the AuthAdapterSpec.php file.

Listing 5 - Spec for successful login

function it_will_return_an_authed_user_if_found_and_password_is_correct(

$service,

AuthedUser $authedUser

) {

$passwordHash = password_hash('password', PASSWORD_DEFAULT);

$service->getUserByUsername('bob')->willReturn($authedUser);

$authedUser->getPassword()->willReturn($passwordHash);

$this->setPassword('password');

$this->setUsername('bob');

$this->authenticate()->shouldHaveType(AuthedUser::class);

}

Diving Deeper

Let’s take a look at what it’s doing. First, we set up a legitimate password hash for our ‘password’ password. Next, we tell the service when getUserByUsername is called with a parameter of ‘bob’, it should return an AuthedUser object (that we are passing in as a mock). We then tell this $authedUser that if getPassword() is called, it should return our password hash. The last three lines are about setting up our adapter with the username and password and calling authenticate. Authenticate should return an instance of our AuthedUser object.

If you run phpspec run at this point, you’ll see there’s a new error that phpspec doesn’t offer to correct for us. This time it’s that the AuthedUser doesn’t have a method called getPassword. This is because our real AuthedUser doesn’t have that method. This points to a good reason to use interfaces in our typehints. In this case, we have a couple of options. We could switch gears and work on the AuthedUser spec to ensure that there is a getPassword method, or we can cheat, and just add this as an empty method. I’ll leave it to you which way you want to go. If we were using an interface instead of a concrete class, we could just add getPassword to the interface. Adding the following line to AuthedUser will get us to the next step, but it “feels” wrong.

public function getPassword(){ }

Now, we should run phpspec again. Now the spec should fail because our AuthAdapter is not working for legit users. Let’s fix that. This test means we’re going to actually need to start using the service that’s been sent into the adapter. If you recall, the constructor is currently empty. We’ll fix that by creating a class property and initializing to the value injected into the constructor. That will look something like this:

protected $service;

public function __construct(AuthServiceInterface $service)

{

$this->service = $service;

}

We can start re-working the authenticate method to do some actual work instead of just returning a GuestUser.

Our authenticate method should now look something like listing 6.

Listing 6 - Updated authenticate method

public function authenticate()

{

$user = $this->service->getUserByUsername($this->username);

return $user;

}

Keep in mind that we’ve just added the minimum amount to make this work. Our adapter works great for users that don’t exist and users that exist and always provide proper credentials. Right now, credentials really don’t matter. We definitely need to add one more spec to ensure that users who exist but don’t have the right credentials, get a GuestUser instead of an AuthedUser. Time to write a bit more spec. Listing 7 shows the new spec.

Listing 7 - Mismatched password should return guest user

<?php

// <snip>

class AuthAdapterSpec

{

// <snip>

function it_will_return_a_guest_user_for_bad_password($service, AuthedUser $authedUser)

{

$service->getUserByUsername('bob')->willReturn($authedUser);

$authedUser->getPassword()->willReturn('badpasswordhash');

$this->setPassword('password');

$this->setUsername('bob');

$this->authenticate()->shouldHaveType(GuestUser::class);

}

}

This spec looks very close to the previous, but instead of returning a good password hash, we’re returning something that will not match a hash for any password. We’re also making sure that the authenticate method will return a GuestUser. Running the spec again will show a failure for our new spec.

At this point, we’ve got no choice but to compare the provided password with the password hash the adapter gets from the service. Time to update authenticate again. Listing 8 shows our updated authenticate method.

Listing 8 - Updated authenticate method

<?php

namespace PhpArch;

class AuthAdapter

{

// snip

public function authenticate()

{

$user = $this->service->getUserByUsername($this->getUsername());

if ($user instanceof GuestUser) {

return new GuestUser();

}

if (!password_verify($this->getPassword(), $user->getPassword())) {

return new GuestUser();

}

return $user;

}

}

We can run phpspec again and see that everything is passing and green. Since everything is passing, we’ve got an opportunity to refactor, that is, change how our code does something without changing the actual outcome. After our refactoring, everything should still be passing. If I look at the authenticate method, it looks like building the GuestUser is redundant – we’re doing that in two different places. We can refactor the code so there are only two return points. One for GuestUser and one for AuthedUser. Listing 9 shows the result.

Listing 9 - Refactored authenticate

<?php

namespace PhpArch;

class AuthAdapter

{

// <snip>

public function authenticate()

{

$user = $this->service->getUserByUsername($this->getUsername());

if ($user instanceof GuestUser ||

!password_verify($this->getPassword(), $user->getPassword())

) {

return new GuestUser();

}

return $user;

}

}

With that refactor in place, the code is a bit simpler, has less redundancy and our spec all still passes. Hooray for successful refactoring!

Conclusion

We’ve run through quite a bit in this article, but only just started to scratch the surface of mock objects and what we can do with them. Phpspec provides some very nice ways to provide mock objects and specify their behavior, so we can test a single class at a time without needing to have or use any concrete classes that may compose our object. It allows us to see if our API makes sense, because if it’s hard to test, it’s probably rather difficult to use as well. I encourage those of you who may have followed along to continue building the other classes we’ve talked about using phpspec and TDD. TDD can be a very beneficial development strategy and phpspec makes it easy to do, if not a bit of fun as well. I highly recommend it.