Leveling Up: Meddling in Middleware

In the past year or two, middleware approaches to writing web applications in PHP have grown quickly in popularity. It’s quite a bit different in terms of how you think about structuring and organizing an application compared to MVC, but it also brings a lot to the table in terms of simplicity and understanding. Today we’ll be looking into middleware, what it means, and how to use it.

PHP has been through a number of fairly major changes over the years, not just in terms of the capabilities of the language, but in the way we write applications using PHP. In the early days, it was common to write scripts “top-down”, mixing code and HTML in the same script. Later, functions were extracted into other files and included or required into the page, but code and HTML still were typically intertwined. With PHP supporting OOP, MVC became a way to clearly organize and structure code where everything had its place. While PHP MVC is not really MVC as far as the pattern was originally designed, the benefits for organization and separation of code and markup are quite good. Other patterns have also emerged, such as ADR (Action / Domain / Responder).

The pattern we’re talking about today is middleware. The terms and concepts are not new – like MVC, they’ve both been around since the 1960s and 70s. Middleware provides a framework for transforming a request into a response. This is typically done via a pipeline which allows middleware to flow from one piece to the next, and then back out again. It’s very similar to how a standard bit of code works with one function calling the next and the next, with the language tracking where we are in a stack. On the way back out, when the inner functions return, control returns to the caller. It is similar in middleware.

Middleware Structure

In general, a piece of middleware will receive a request and a way to call the next piece of middleware in the pipeline. In some frameworks, they also receive a response object as well. If you’re interested in the debate over which way is superior, feel free to take a look at the PHP-FIG mailing list.

In any case, what I mean is that middleware will typically have a signature like one of the following:

function __invoke(Request $request, Response $response, $next) : Response

- or -

function __invoke(Request $request, $next) : Response

You may find frameworks that use method names like handle or process or something other than __invoke, but the idea is they’ll receive a Request and a way to get to the the next middleware, and they’ll return a response. In some frameworks, the Response is provided as an argument on the way in.

A pipeline can be configured with a number of middleware pieces. Each middleware can be responsible for a single change or operation, or they can do more. In order to make things simple, though, my recommendation is not to do too much with any individual piece of middleware. As I mentioned before, the flow through the middleware typically passes in through each piece, moving to the next until the final middleware is reached. It returns a Response object which is passed back through the middleware in the opposite order in which they were called. This gives the original caller an opportunity to manipulate the request on the way out. In the case of an error happening, the flow can actually detour off into a set of error handling middleware.

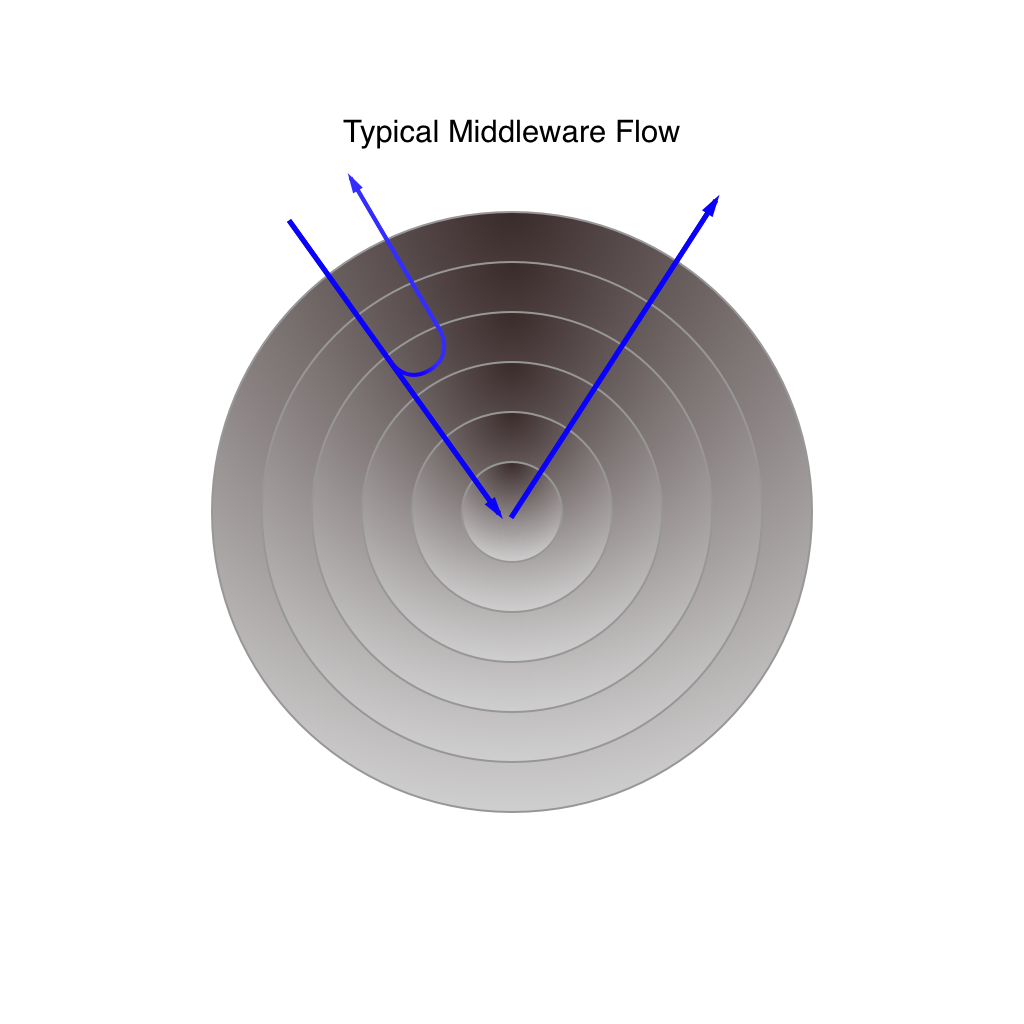

Figure 1 illustrates a couple of ways a flow may work. Consider each circle as a piece of middleware. The request comes in through the outermost or first piece of middleware which can manipulate the request in some way and then pass it to the next level. This proceeds until the final piece of middleware on the stack (the centermost circle) which then returns some kind of a response. It flows back out through each piece of middleware, each of which is given a chance to manipulate the response in some way. Alternatively, middleware can determine that it’s not going to pass control on to the next piece of middleware. Imagine the third circle was a validator of some kind that determined the request could not possibly proceed. Rather than pass on a broken request until it fails, we can stop processing early by returning a Response or an error object. This could be done via throwing an exception, or just returning a Response object which represents the error that needs to be addressed if the caller wants to have the request succeed. This is represented by the curve to return back out in the third circle.

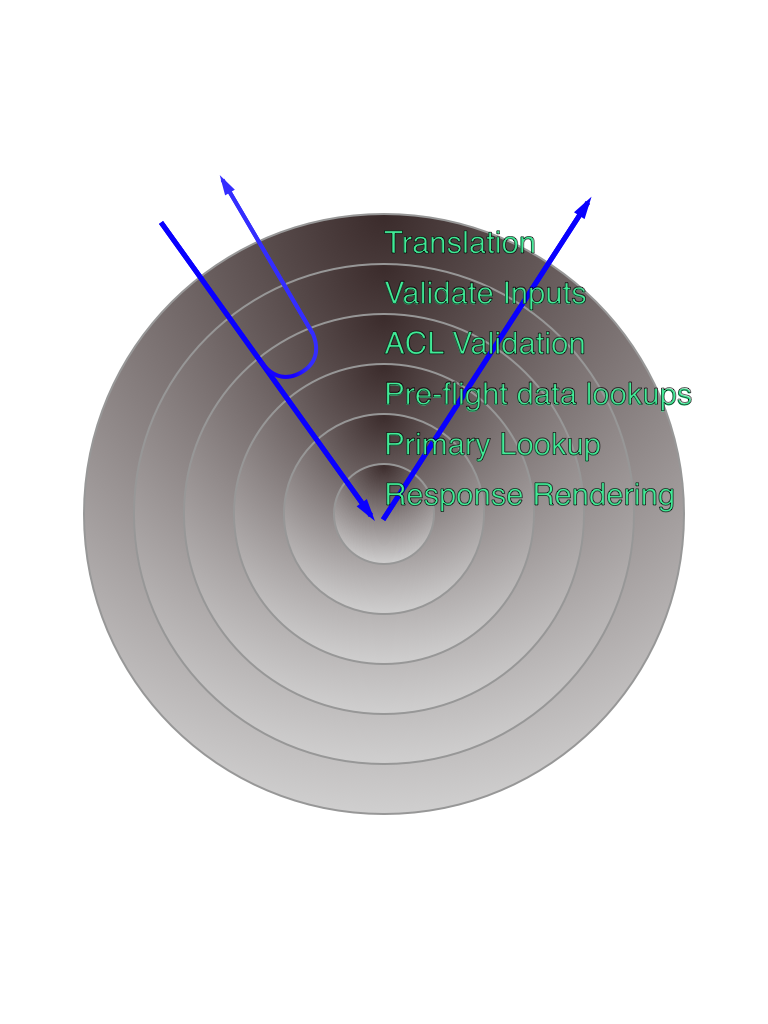

Figure 2 shows some made-up but feasible uses for middleware. On the outermost circle, we have a translation service. Presuming we have some magical technology that could translate any outgoing Response, this would be a good place for that middleware. It means that on the way in, it does nothing, but on the way out, whatever is returned could be translated into whatever language it needs to be. This would include everything from a fully baked and proper response, to any errors that may have happened in the subsequent levels.

The second layer, we have input validation. If the request doesn’t include the proper inputs, we can determine early on that the request will be an error. We can make that determination and return early. The response would be translated as appropriate, and we don’t end up doing any extra work.

If the inputs are valid, it will pass through to the ACL (access control list) layer where we could determine if the user should be allowed to access the resource. If not, we can return early with an error indicating that the user is not allowed to do whatever they are trying to do. In this case, the ACL error would return back through the Validate Inputs middleware, but remain unchanged until it got back to the Translation level.

Depending on your preferences, the ACL level could be swapped with the input validation middleware. This would allow you to kick an unauthorized user out of the application sooner, and avoid even doing the work of validating inputs. If the work we’re doing is considered open or public, the ACL layer could be omitted, the same way the validation layer could be left out if there’s nothing to validate. The ACL level itself could be its own middleware pipeline, splitting the work into smaller, more discrete units. This could include a layer to authenticate a user, a layer to load permissions for the user, and a layer to figure out what permissions are required for the route, and another to determine if the permissions the user has match the ones they need.

Assuming everything is good to this point, we can move on to a theoretical “pre-flight” set of data lookups which could include database or API calls in order to make the “meat” of the request possible. This could move into the main lookups or retrieval, followed by another level that would render the response as JSON or something else. This level could, again, be another pipeline which determines what type of a response is expected and formats the data accordingly.

Needless to say, there’s a lot of options. Each piece of middleware can be simple and straightforward, doing only a single thing on the way to transform a request to a response. This means that each piece of middleware can be easily unit-tested. It also means there is a significantly simpler mental model for what will happen on the path to transform a Request to a Response. There’s no need to try to remember all the events or pathways code may take to get through an application.

Incremental Building

Let’s imagine we’re trying to build an API that will allow a user to retrieve a filtered list of United States state abbreviations. We want to ultimately be able to filter a list, as well as returning the list in a couple of different output formats, ensuring only allowed users can get these top secret state abbreviations. That’s quite a few things, but we can approach each one, in turn, incrementally adding functionality by wrapping middleware in other middleware that gives our application more functionality.

To start, we need to be able to return data. We can fake this part for now.

class StateReturner

{

public function __invoke(Request $request, Response $response, $next)

{

$list = ['CA', 'CO', 'CT'];

return $next($request->withAttribute('stateList', $list), $response);

}

}

The StateReturner class is providing data into the Request object and passing it on. It is not responsible for figuring out how the state codes will be represented in the final output, it’s only job is to provide the state codes so that some other piece of middleware will be able to process it, ultimately ending up with proper output.

As a side note, the code examples I’m giving are not targeted to work under any particular middleware framework, but with slight modifications in one direction or another, they theoretically could work with quite a few of them. The Request and Response objects I’m type hinting would follow closely with PSR-7s ServerRequestInterface and ResponseInterface.

Suppose we add this to our pipeline as the only piece of middleware. We’re won’t see much since nothing is yet returning a Response object. With only this piece of middleware, we need something else that can transform it into data that can be rendered.

Pipeline:

[ StateReturner::class ]

Let’s build something that will take our stateList and put it in the Response.

class JsonStateOutput

{

public function __invoke($request, $response, $next)

{

$realResponse = $next($request, $response);

$stateList = $request->getAttribute('stateList') ?? [];

$realResponse = $realResponse->withHeader('Content-type', 'application/json');

return $realResponse->getBody()->write(json_encode($stateList));

}

}

Now we have a piece of middleware that will take the stateList value from the request, JSON encodes it, and puts it into a response it returns. Even though there’s not a lot of code, I feel it’s worth it to step through each line to make sure we’re on the same page.

Starting out, we call the next piece of middleware and store its return value (a response) in $realResponse. I named it that to make sure it was distinct from the passed in $response parameter. Additionally, I usually try to avoid changing the incoming parameter variables in my functions unless the purpose of the function is a side-effect.

We don’t know what else may come after this middleware, but it doesn’t matter. It could be the final middleware, in which case the value of $realResponse will be the same as the incoming $response parameter. It could also be something else, or a bunch of other middleware.

Next, we retrieve the stateList from the $request. This means that in order for this to work, the list of states must be already in place when the JsonStateOutput middleware is called. That means it should come after the StateReturner middleware:

Pipeline:

[ StateReturner::class,

JsonStateOutput::class ]

We make a new Response object that includes the proper content type header. We then take that new Response object, create another new one based on that, but now with the body content added of a JSON list of ‘C’ states.

At this point, the application will run through StateReturner, placing the list of states starting with ‘C’ in an array stored as an attribute of the Request. Then we invoke the next middleware which is the JsonStateOutput middleware. It, in turn, immediately passes control on to the next piece of middleware. The JsonStateOutput will do its job is done on the way back out. Once the response is returned, the JsonStateOutpu class augments it with a body with that list of states rendered as JSON. That response is then returned to whatever piece of middleware called the StateRunner.

At this point, we should be seeing a JSON list of states that start with ‘C’. Each of these middleware classes we’ve built so far is easily unit testable.

The Order of Things

With this style of middleware, it is certainly possible to manipulate and change the response on the way in. However, I’d highly recommend avoiding that. It takes some discipline, but there’s a good reason. If JsonStateOutput had placed the JSON in the response before calling $next, then the next piece of middleware could completely remove or mess up the JSON body. On the way out, though, it’s another story. We’re moving from least important or critical middleware to more important.

If we were to follow the other middleware pattern, specifically the signature that doesn’t have the Response object in the incoming parameters in its signature, we wouldn’t even have the option to modify the response on the way in. The pattern I feel is best for middleware is to work with the Request on the way in, meaning before the call to invoke $next, and to work with the Response on the way out, that is, after the call to $next. This means that if your middleware is only doing one thing (which it should), then it would likely fall into one of two patterns.

// Incoming middleware that manipulates the Request

public function __invoke($request, $response, $next)

{

// Make changes to $request

$newRequest = $request->withAttributes('whatever', 'you want');

return $next($request, $response);

}

- or -

// Outgoing middleware responsible for changing the response

public function __invoke($request, $response, $next)

{

$outgoingRequest = $next($request, $response);

// Figure out modifications

return $outgoingRequest->withChanges();

}

In the example code, StateReturner follows the incoming side, while JsonStateOutput follows the outgoing pattern. Again, rarely should a piece of middleware need to modify the incoming Request and the outgoing Response. I’d also argue that other than making it easy to return a response without needing to instantiate it, the incoming $response argument should probably not be used unless you know a piece of middleware is going to be the final middleware.

Multiple Output Formats

In order to be able to return different formats for the data, we need to figure out what the Request is asking for. We could make another couple of middleware for XmlStateOutput and CsvStateOutput. Each of those could look into the request and process the “Accept” header. If it didn’t match the appropriate type for each middleware, they could essentially become pass-through objects. However, this means that processing of the Accept header would be duplicated in each output rendering middleware. Instead, we can create a piece of middleware that would process the Accept header and set an attribute on the request before sending it through to the rest of the stack. Each of the output middleware could then look something like this:

class JsonStateOutput

{

public function __invoke($request, $response, $next)

{

$realResponse = $next($request, $response);

// **** NEW ****

if ($request->getAttribute('outputType') != 'json') {

return $realResponse;

}

// **** END NEW ****

$stateList = $request->getAttribute('stateList') ?? [];

$realResponse = $realResponse->withHeader('Content-type', 'application/json');

return $realResponse->getBody()->write(json_encode($stateList));

}

}

The conditional ensures that JSON should be returned. That means before we get to this piece of middleware, we should have another middleware that determines the output type from the Accept headers and sets the outputType attribute as appropriate.

Our pipeline could look like this:

Pipeline:

[ NoOutputError,

GetOutputType,

JsonStateOutput,

XmlStateOutput,

CsvStateOutput,

HtmlStateOutput,

StateReturner ]

There are still additional pieces that would need to be built. Obviously, we’d want to replace the StateReturner with something that can return more than three state abbreviations. If we want to ensure only authorized people can utilize our state abbreviations API, we’d need to build a set of authentication and authorization middleware, as well as potentially some to deal with ACL.

We’d need to write some code to process the query string parameters into a filter that could be used to limit the states that are returned.

We may want to build some middleware that could modify the JSON output to add HAL or other metadata to the response. We ould definitely want to revisit the StateReturner so that it gets the list of state abbreviations from a database or a file. Depending on if we went with the database or a file, we may have another piece of middleware that would come into play for actually filtering that list down.

In short, we have tons of possibilities, and each one of the individual middlewares should be pretty simple. Each modification we make can be done incrementally, moving from one working state to another. Instead of the path many applications take, where new features get tacked on and slammed in wherever they appear to fit, eventually resulting in a pyramid of doom and tech debt, waiting to collapse under the weight of its own sadness (Thanks, Chris Pitt), we can build small, incremental, loosely coupled, easily testable bits of code.

In our example so far, we can assume there’s some kind of route which points to this pipeline. In addition to route specific middleware like this, most frameworks will allow you to pipe in middleware that will automatically be executed before or after any route related middleware are executed. This would potentially be a good place to inject middleware for authentication, authorization, error handling, output rendering and any other generic and non-route or non-resource specific code we may need.

Because of this, if we build the entire application through middleware, there will be multiple endpoints, routes, and functionality. We can upgrade and add functionality across the board just as easily as adding a feature to an individual route or API.

Middleware Frameworks

There are a number of current PHP frameworks for building middleware applications. From Zend, there’s the Expressive framework and Stratigility. Additionally, Zend Framework 3 provides middleware execution by default now. Additionally, there’s Slim, Relay, Equip, and Stack. If you’re a fan of Symfony, Silex provides a way to run middleware with Symfony components. If you prefer the Laravel ecosystem, Laravel can do middleware as well. In short, there’s a lot of options, you just have to choose the one that fits best with what you’re familiar with or what you want to learn. Each of the frameworks brings something a little different to the table. Expressive, Slim and Stratigility appear to work in nearly the same way. Several of these are based on PSR-7, each providing their own way to handle HTTP messages.

Conclusion

Building applications following the middleware pattern is a great way to build complex applications while keeping the code small, simple, maintainable and testable. The middleware pattern allows for an easy way to mentally track through and understand the flow of an application. It allows for fast execution because there’s little overhead. Pieces of middleware can be reused or even automatically piped in for any or all application routes which provide a convenient way of upgrading and adding functionality with minimal effort. I’d highly recommend checking out one of the middleware frameworks or looking more into middleware and seeing how it could work for you.