Leveling Up: Building Better Objects

Last month, we started talking about objects. Joseph Maxwell’s article talked about several common design patterns for objects, including factory, strategy, and chain of command. Additionally, he talked about dependency inversion. This month we’ll continue talking about how objects should be built and why using objects to build applications has advantages over the old style of building procedural pages.

Why Objects?

Classes and objects help us organize code. In old-style PHP, the code is typically organized in folders and subdirectories. Sometimes, when the same bits of code are found over and over, these may be extracted out into a function. When these functions are found to be repeated in file after file, inevitably, someone decides that these functions should all be available in the same place and some file like functions.inc.php or funcs.php or some similarly named collection of files is created. It’s then required all over.

The problem is that there’s usually not a lot in common between these functions. Some may be used on nearly every page, while others are used in only a handful. And yet, without any sort of discrimination or limitations, all these functions need to be loaded in order to use any of them.

Objects are a combination of data and behavior. In an object, we call the “data” fields, properties or attributes. We tend to call the behaviors “methods”. Whereas a function will have access to the parameters that are passed in along with the occasional global (eww!). A method on an object, however, can work with parameters that are passed in, globals (eww!), as well as properties on the object itself.

In fact, most methods will utilize properties on the object more than anything else. I think I’d go so far as to say if there’s a public method in a class that doesn’t use $this then perhaps the object is more of a function bucket than a well-designed object. A common counter-example I’ve seen, however, are factory classes. The ones I tend to see look like this:

class SomeSortOfThingFactory implements FactoryInterface

{

public function createService(ContainerInterface $container)

{

$dep1 = $container->get(Dependency1::class);

$dep2 = $container->get(Dependency2::class);

return new SomeSortOfThing($dep1, $dep2);

}

}

But Really, Why Objects?

So far, I’ve not really talked about why we should use objects – what the benefit is. Since objects combine behavior and data, it allows certain affordances that we don’t have when we’re dealing with PHP primitives.

Suppose you’ve got a bit of code that receives some information from the query string or posted form fields and does things with them. Perhaps it looks up some information in a database, or it performs some calculations on them. With normal use of $_GET or $_POST to retrieve these values, we’re working with an array. If you’re trying to avoid PHP spewing notices, you have to first check for the existence of a key in those arrays in order to use the value that may or may not be there.

$filter = isset($_GET['filter']) ? $_GET['filter'] : 'default';

With PHP 7, we now have the null coalescing operator which can simplify the statement above:

$filter = $_GET['filter'] ?? 'default';

If we don’t do any of these and just try to use $_GET['filter'] without checking, we’ll get a notice from PHP:

$filter = $_GET['filter'];

Notice: Undefined index: filter in /path/to/file.php on line 42

With object-oriented design, we can build objects don’t have to check that a field exists in an object, or that it’s an instance of a certain type. We can be assured that by the time we’re working with the object, everything about it will be as expected and as we wanted.

This means instead of dealing with $_GET or $_POST, we could work with a request object:

$filter = $request->get('filter', 'default');

I haven’t shown you any code to make the request work, but it’s not too hard to build.

Objects Are About Messages

The power of objects comes from being able to compose them together and allowing them to communicate to allow for more complex and powerful behavior. Methods, specifically public methods, are the definition of the messages you can send to an object. If you think about it, this makes sense. While the methods define the functionality and behavior, the caller of the method is the one telling the object to do something.

The messages are the methods along with any parameters we provide. Let’s take a look at what I mean.

class Greeter

{

public function sayHello()

{

return 'Hello, World!';

}

}

In this case, our Greeter class has a single public method, and thus, a single message that can be sent to it.

$greeter = new Greeter();

$greeting = $greeter->sayHello();

Suppose we update the class so that sayHello takes a parameter:

public function sayHello($who = 'World')

{

return "Hello, $who!";

}

With this update, the previous example still works, but the sayHello method can now say hello to a lot more. In fact, any parameter for $who that is, or can be rendered as a string will work. This means we could pass in names, numbers, or even other objects that define a __toString() method. But what happens if we passed in an array, or a database connection, or an object that didn’t have __toString()? In that case, we’d end up with an error.

$greeting = $greeter->sayHello(new stdClass());

For this we get the following error:

Catchable fatal error: Object of class stdClass could not be converted to string

As of PHP 7, it’s now possible to type-hint almost everything. With PHP 7.1, this includes type-hints on the return types of functions and methods. If you can, and it does take some practice and discipline, I would recommend using these any place you can. They can eliminate a lot of boilerplate checks on your parameters and ensure your code is smaller, simpler, easier-to-test and more robust. It also will allow your IDE to present issues and bits of code that are likely to be bugs before you even run your code.

public function sayHello(string $who = 'World'): string

{

return "Hello, $who!";

}

Now if we were to try to call sayHello with the object as before, we get a slightly different error:

Fatal error: Uncaught TypeError: Argument 1 passed to Greeter::sayHello() must be of the type string, object given

This will be followed by a stack trace indicating how we got to a place where we made a method call using an object when the code expected a string.

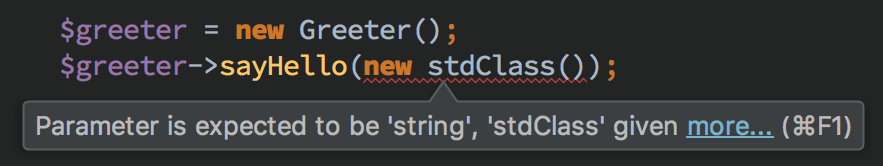

In PHP Storm, without even running the code (but with strict types turned on), we’d see something like this:

So, anyway, back to messages. In the examples above, we have an external user sending a message to an object. Messages can also be sent from one method to another method, from a method to itself (recursion), from an object to its parent or child, to objects passed in as parameters, or to an object’s dependencies. It is these relationships where the real power comes in.

Delegation

In the last article, and probably in a few before that, I said: “If you have to use ‘and’ to describe what your class does, it’s doing too much.” This is essentially a restatement of what’s commonly known as the Single Responsibility Principle. It says that every class or module should have a responsibility for a single part of the functionality provided by the software and that responsibility should be entirely encapsulated by the class. In was introduced by Robert C. Martin in Principles of Object Oriented Design. Software applications are often quite complex. There are many “moving parts” and aspects that need to be handled, checked and controlled. So how, then, can we ensure that a class has only one responsibility? This is where delegation comes in.

It is often said that there are two hard problems in computer science - naming things, and cache invalidation. The joke that continues this by including “off by one errors”. Part of the problem with determining what the purpose or responsibility of a class falls into the hard problem of “naming things”. Coming up with descriptive and accurate names for classes is hard. Determining where the line is that delineates where the responsibility of one class ends and the next begins is hard. Sometimes, it may be better to build a class that does too much and then refactor out different responsibilities to different classes later.

This leads back to delegation. This means that as much as we can, our classes should delegate work to another class.

Imagine you have a controller class with the responsibility of showing a user their preferences. Let’s look at what needs to happen in order to do this.

- Determine if user is authenticated

- Retrieve ID of user to look up

- Connect to the database

- Issue the appropriate query to look up the preferences record

- Determine if a record was found

- If a record was found pull out the relevant fields for display

- Display the record

There’s a lot going on and if we do all of this in the controller, there’s really no way to describe without using “and”. So we need to delegate.

If we can allow another class (or set of classes) to determine if the user is authenticated or not, then that’s one job off our (controller’s) plate. However, we need the result of that to move forward, so whatever determines authentication will need to pass in the user object to our controller. I’ll forego breaking down the authentication at this point as I’m trying to concentrate on the controller and its directly related objects.

Assuming the authenticated user is made available to our controller we the user id from it. Instead of providing the entire user object, it could instead provide the user id if that’s all we needed. So next up, we have to connect to the database. This sounds like a job for something else entirely. In fact, some other object that doesn’t even necessarily know about the database at all could be used to retrieve a user.

We could have a sort of user service which itself encapsulates objects which encapsulate the database connection, the query, any sort of object hydration, etc. All we really need in our controller at this point is that whatever does all this work ought to give back the user preference record. Once the controller has that record, it can delegate to some sort of view or view model object to render the actual HTML.

After this, most of the responsibility is delegated. The only things left are to either ask a user service for the record and shuttle that data into a view or view model.

So now we have this:

- Determine if user is authenticated (delegated)

- Retrieve ID of user to look up (potentially delegated, probably provided)

- Connect to the database (delegated)

- Issue the appropriate query to look up the preferences record (delegated, controlled by controller)

- Determine if a record was found (possibly delegated)

- If a record was found pull out the relevant fields for display

- Display the record (delegated)

There are only one of those tasks left which are not delegated. It’s certainly possible there could be a class that has the job of converting from a user object into a view model object. In that case, we could delegate that responsibility as well.

This means delegation, our final action method could look like the following:

public function fetchById($id)

{

$preferences = $this->userPreferences->fetchById($id);

return new ViewModel(['preferences' => $preferences]);

}

There’s not a lot to it. If user authentication is handled elsewhere, then we can assume we won’t get into this method if we’re not authenticated. If the id is provided (via the parameter) then we don’t need to worry about that responsibility either. Presumably, the SQL connection and query are handled by the $this->userPreferences object, or delegated on to other objects from it. That userPreferences dependency would be injected into the constructor when the controller was created.

The userPreferences service would be responsible for making a determination about what to do if there was no record found. It could throw an exception, or potentially return an object following the null object pattern. The controller retrieves this object, passing it through to a ViewModel which is handled outside the fetchById action.

Each object has a purpose. Together they come together and help to solve a problem. By building an object with the responsibility of fetching user preferences (even if that’s done via delegation to a group of other objects). If we needed to build a utility that could look up user preferences and display them as a command line utility, we can reuse the userPreferences object. That object doesn’t know anything about how the data it returns will be used, it just knows how to retrieve a record from a given ID.

Depending on how that object itself were structured, it may be possible to seamlessly switch it or its dependencies out with something else that could retrieve a record from a CSV file, or an API or anything else. The rest of the system wouldn’t need to change. Caching layers could be introduced with minimal changes.

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the ability for us to treat some aspects of what an object does as a black box. It is information and functionality hiding. It’s counter-intuitive, but knowing less about what the code is doing is empowering. What I mean by this is that the less one class has to know about how another class works, the better. As a developer using classes you didn’t build, the less you have to know in order to use them, the better.

In the controller example above, the only thing our controller needs to know about the user preferences object is that it has a method (or accepts a message) asking for user preferences given an integer identifier. It will return back a user preferences object. Note that in the description, nothing was said about a database. In fact, the controller doesn’t need to anything about a database in order to use that service.

interface UserPreference

{

public function fetchById(int $id): UserPreferenceModel

}

Essentially anything that implements the interface above could be swapped out with something else that also implements it and our controller would not care. It could be a test double or mock object, or with a different implementation that retrieves user preferences from files, APIs, NoSQL databases or even a hardcoded list right in the code.

As another example of why encapsulation is important is in the use of everyday objects. If you drive, you’re aware that roughly speaking, the gas pedal makes the vehicle go faster, the brake slows it down, and the steering wheel is used to aim the car in the desired direction. The car hides a lot of what it does and how it works from us, and we are better for it.

The gas pedal interface is simple – we can press on it or release pressure on it. This input is used to help determine how fast the car will move. However, the implementation differs from one vehicle to another. In older cars, pressing the pedal moves a lever which pulls a cable that opens valves that release more fuel into the engine, causing it to turn faster, etc. etc. In some cars, the pedal is really providing input to a computer which determines how much electricity to provide to the motors turning the wheels. In certain cases, the computer may decide to completely ignore the input. In the car I drive daily, I have the ability to hold down the brake which through a series of mechanisms, holds physical pads against a part of the wheels, preventing them from turning. At the same time, I can press the gas which makes the engine rev, passing power to the wheels. I can feel the car try to surge and hear the engine pitch increase. However, in my wife’s car, a hybrid, doing the same thing doesn’t result in a surge or any increase in engine pitch. In most cases, the engine doesn’t even turn on at all. The computer decided that if both inputs are pressed, the gas pedal will be ignored.

The steering wheel is another interface that hides a lot of complexity. In older vehicles, turning the wheel literally moved gears and racks and pinions and any other sort of mechanical system which in turn eventually would cause the wheels to turn in the desired direction. These systems got more complex as power steering was added, and now, with the latest models of Tesla vehicles, the wheels can turn without any input on the steering wheel at all. The computer, along with the various vision and sensor inputs can make the determination that the cars need to move in one direction or the other. In the not too distant future, the interface for the car, one that has not really changed much at all since its invention may undergo a pretty radical change. Instead of the interface being gas, brakes, and steering, the interface may be voice input where the user of the vehicle simply speaks their destination and the car determines everything that needs to happen in order to deliver the user to the destination safely and quickly.

Conclusion

By delegating work to other objects, we can help to ensure that our objects only have one responsibility. By hiding data and functionality, we make it easier to be able to swap out certain pieces of our application without the need to rewrite large portions of it. The concepts of delegation and encapsulation are powerful in OOP and we’ll be utilizing them later. In the coming months, we’ll continue to explore objects, how they work, how they fit together, how they can communicate and how you can use them to make better software. See you next month.