Leveling Up: Building Better Bug Reports

One of my favorite quotes about programming comes from Edsger W. Dijkstra. It says, “If debugging is the process of removing bugs, then programming must be the process of putting them in.” It indicates the maxim that as long as there is code, there will be bugs. Of course, we want to minimize the number of bugs in our code. Understanding what the desired behavior of our software is, and how that differs from the actual behavior is the key to understanding what the bug is and how to fix it.

What are bugs?

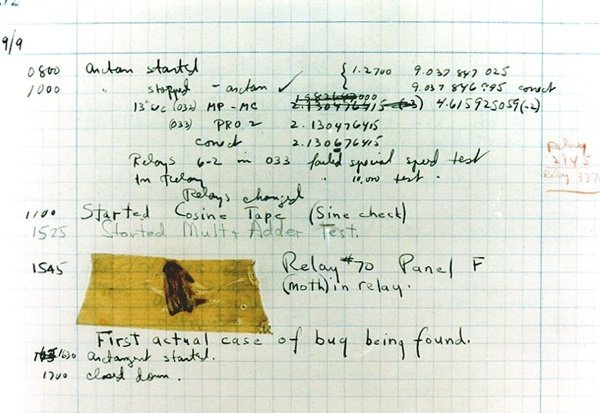

Over the past two months, Vesna Vuynovich Kovach has been writing about the history of women in computing in this magazine, so this story should be familiar. On September 9, 1947, Admiral Grace Hopper, recorded the first instance of a computer bug in her log book. In her case, the room-sized computer, the Harvard Mark II, had a program that was not behaving properly. After careful inspection of the literal inner workings of the computer, she found and removed the bug in her program. It was a actual moth that was caught in relay number 70 in panel F of the computer. Figure 1 shows the log book. See if you can spot the bug.

Since then, undesirable or errant code behaviors have received the label “bug”. In some bug trackers, the term is labeled “defect”, but the bottom line is that whatever you call it, chances are you want to be able to find and remove them from your code. They are problems in the logic and working that prevent correct and proper execution of a program.

According to Admiral Hopper’s log book, she had started a multi-adder test. I imagine somewhere along the line, probably pretty early in that test run, she noticed that something that was supposed to add up properly, wasn’t. At this point in time, programming was much closer, literally, to coding on the bare metal. I imagine she looked at the tests that worked and looked at the ones that didn’t and started tracing through the code, into the actual hardware. This process likely involved following physical wires and cables until the bug was found in the relay. The bug was then removed, the tests re-run and everything passed and she stopped and went home at 5 PM.

Imagine how different this scenario could have been today when we are able to (mostly) take for granted that the hardware is doing what it should. If this multi-adder code was in a library, it could have hidden or internally corrected for the bug. The problem with removing these bugs then is that if the code is relying on them being there, then removing it can cause breakage. It’s also important to note here that when tracking down and removing bugs, it’s best to start with our own code and exhaust the possibility that the bug is in our own code before moving to blame the framework or the language. For the vast majority of people, the bug will be in their own code, not in the framework or the language. I’ve seen loads of bug reports where the developer thinks they’ve found a problem in a framework or the language when what they actually have is a bug in the code they have written.

Bug Reporting

In my article last month, I mentioned changing bug tracking software if it was not helping build software or was interfering with your processes. It was not intended to be a promotion or endorsement of any particular bug tracker, but rather to find and use a bug tracker that works for you and your processes. Don’t let bad tools get in the way of improving your process.

We’ve all likely seen horrible bug reports:

It doesn’t work.

In this case, we have no idea what doesn’t work. Is it the entire site is gone, signup is broken, custom reporting functionality is not right, the dashboard isn’t rendering or the user’s wi-fi is down? We have literally no idea of what they are telling us is broken and little hope of being able to help.

Your site is broken

This report is not much better than the one above. It could be anything still, up to and including problems on the user’s computer or network. Without more context, helping the user out will be very hard. Giving this report to a developer will be an exercise in frustration for them and whoever reported it.

The internet is down

First of all, no, probably not, unless the Mirai botnet has taken over a lot more cameras and toasters. In all likelihood, this report is indicating some sort of an issue that exists entirely on the user’s side. A good indication of this is if they entered a bug like this through email or through your bug tracker directly. If the internet were actually down, those wouldn’t have worked so well. Again, in all likelihood, the user is having a problem with one aspect or utility but doesn’t know enough about how things work to properly report the issue.

Building Good Bug Reports

In my opinion, there are three critical properties of a good bug report. A good bug report is one that will help the person fixing the issue track down the problem quickly and easily, identify what the issue is, and fix it.

The first aspect of a good bug report is a clear and ideally minimal set of steps that can reproduce the issue. This is not always possible to provide, but if it can be provided, it can be invaluable in tracking down a problem. Ideally, this would be a set of steps from some known or common starting point which will result in the issue occurring. For example:

- Clear browser cookies

- Go to the homepage

- Click on Login menu

- Provide valid credentials

- Click login button

In this case, as a developer digging into this, we’ve now got a couple of reproducible steps that should cause the problem to happen. It might be that not all of these steps are strictly necessary to cause the problem, but since there are only a few steps, it’s not that big of a deal. We don’t necessarily need the person reporting the bug to understand everything about what is happening. In some cases, the number of steps to reproduce may be large. Many of the steps may be unnecessary, but if there are steps that can cause the problem, then we’re already starting off in a better place than most bug reports.

In some cases, a bug report with a huge number of steps may be what the developer needs. I remember one such case where the bug filed by the QA Engineer appeared to involve clicking on nearly every navigation link in the application. I mentioned it in passing to one of the developers. My recollection of the exact click path of the bug was sketchy at best, even at the time and involved saying something like “and then you click on this, and this, and then do that about 19 more times on other parts and then the app stops responding.” It turns out that my inexact relaying of the bug report to the developer was all he needed to theorize what the problem was. It turns out that clicking through two specific navigation items caused the problem. They both loaded the same component into the DOM and that component had the say HTML id. Once that was in place, code that assumes that ids should only exist once in the DOM stopped working and the application stopped responding to clicks.

The second aspect of a good bug report is to list what the expected result is. Often this will be short and to the point - “The user is logged in” or “The site doesn’t crash and show a stack trace to the user” or “The user is greeted by name”. If the expected behavior is short and to the point, many developers will be able to make the logical leap to guessing what the actual behavior was – that is, whatever the expected behavior was, negated.

The third critical piece to a bug report is the actual result. While it may be possible, in many cases, to guess that the actual behavior is the expected behavior, but negated, this is not always the case. Providing the actual behavior explicitly will help the developer sort out what is happening. Without it, the developer may run into a different bug or what they think is a bug, and then fix that behavior, only to have the bug report re-opened. This leads to frustration on the part of the bug reporter and the developer since work is being done, but the desired result is not happening.

Missing Features Are NOT Bugs

I want to step back for just a moment to reiterate some things I’ve said in previous articles. It is important that we do not categorize features that have not been implemented as bugs. Suppose we look at the bug report from above, specifically the one that indicates that the user should be greeted by name once they are logged into the application. Under different scenarios, this could be seen as a bug report, while in others, it’s most definitely a feature request.

If the site has never greeted the user by name, chances are you’re looking at a new feature request, not a bug. That’s not always the case, but in general, if the application never did the behavior that’s being referenced in the bug report, it’s probably not a bug report but a feature request. Properly categorizing features versus bug reports is important because it can and will affect team morale.

That being said, I can understand the argument that if there were requirements that the site greet the user by name, and the site is delivered without that functionality, it could be seen as a bug. I’d argue that greeting the user by name should have been a separate feature request all on its own, rather than bundled in with a bunch of other functionality descriptions and requests. This would indicate if there was a ticket, story or feature request for displaying the logged in user’s name and the site doesn’t do it, then that functionality was never delivered. If it was delivered and worked at some point, but no longer does, then it would almost certainly qualify as a bug.

Bug Priorities and Severity

Bugs in software are a fact of life. We will never be able to remove all of them from any given (non-trivial) piece of software. We should work toward removing every bug we can from our software. However, not all bugs are created equally. Some bugs have a relatively minor impact on the site or its users. A bug involving a spelling error or a link being the wrong color shade or a navigation item being in the wrong order is certainly a different level of impact that users not being able to log in or users seeing someone else’s information after they log in or the site crashing and displaying a stack trace if they hit the back button on the browser.

Most bug tracking software will have a concept of priority as well as the concept of severity. It’s important to understand what these mean.

The severity of a bug indicates what its impact is. This could include data loss or corruption, monetary loss, crashing, causing areas of functionality to be unavailable, etc. Often the severity of a bug will be rated with terms like critical, major, moderate, minor or cosmetic.

For priority, we’re talking about the order we should fix the bugs. Typically these are going to use words like low, medium or high. The reason to have these separated is that there is not necessarily a direct correlation between the severity and the priority of a bug. You could, for instance, have a bug where there was a typo in the motto in your company’s logo image. The bug may be categorized as cosmetic severity, but with a high priority. This indicates that while there’s no data loss or crashing, it is important to resolve the issue right away. Conversely, you may have a critical bug that breaks data, but it only happens for one person in your QA team because they are running IE 6 with a weird plugin and admin privileges. It’s still important to fix it, but you may have the option of telling your tester to stop doing that until you can fix the issue.

Let’s take a look at what these levels of severity and priority mean.

Severity Levels

-

Critical - This severity level indicates that the bug causes a crash in one or more areas of the system. The bug can data loss or corruption. There is no acceptable workaround or alternative path to allow a different way to accomplish the same task.

-

Major - This level can be seen as essentially the same as critical, that is, a crash or area of the system is not usable, but there is a usable workaround that allows users to continue and complete their work, but maybe not in an optimal way.

-

Moderate - At this level, we are not crashing, but the system may be producing incorrect or inconsistent results.

-

Minor - A minor defect would not result in a crash, but a bug at this level could affect the usability of the system. There should be an easy way to work around the defect to obtain the desired result.

-

Cosmetic - If the bug involves the look and feel, but doesn’t involve any crashing, data corruption. At this level, we’re really talking about things like typos, incorrect images or colors.

Priority Levels

-

Low - Fixes for low priority items can be delayed or deferred until later. They are annoying, but more serious issues should be fixed first.

-

Medium - Medium priority bugs should be fixed during the normal course of development. It should be fixed soon, but it isn’t something that needs to interrupt or change the normal flow or schedule of deployment.

-

High - High priority issues need to be resolved as soon as possible. These are the bugs that should or can be deployed outside the normal deployment schedule.

Some examples of bugs with varying severity and priority levels:

High priority and critical severity - This is a bug which happens in the normal and common use of the application. It will prevent the user from using the application.

High priority and low severity - This could be a spelling error or typo on the front page or start of the application. It’s something that everyone will see, but it’s not affecting the functionality of the site. It is important that these be fixed right away to maintain the appearance of professionalism, but the bug is not really causing problems with using the application.

Low priority and low severity - These would be cosmetic issues that are not seen or commonly encountered. It could be a typo in the middle of a paragraph of text in the help section of the site. Perhaps it’s something that people don’t often encounter, and if they do it is not going to affect their usage of the application.

My Thoughts on Defects

In general, I try to treat any defect with a higher priority than what it was assigned when it was created. What I mean by that is that if there are any defects reported against my application, I like to move them up in priority so that all known or reported defects are resolved before working on new functionality. I like to treat any bug that causes a crash or stack trace, no matter how bizarre, obscure or unlikely it is that the user can cause it to happen, as a critical issue. By doing this, I’m keeping defects to a minimum. There will always be more bugs found, but by trying to fix all bugs before building new features, I don’t have to worry about running into an insurmountable wall of bugs that eventually bring the application to a grinding halt.

I try to be unmerciful with bugs. The applications I’m currently building, are typically API driven. This means if we have new functionality to add to an application, we’ll build an API that allows that functionality to work. I’ll push that code into the application and give the QA team information and documentation about how the API should work. Keep in mind at this point, there’s absolutely nothing that’s using or relying on this new API. However, if and when bugs are reported, I jump on them, eager to fix them and provide the most solid API I can before I turn it over to my UI team to connect with and use. That gives both them and myself a lot of confidence that what we’ve built will be solid and is not likely to change much. It also gives them confidence that if they run into an issue when integrating with the API that we’ll be quick and responsive to fix anything they found.

Making Sure It Never Happens Again

If you’ve been reading my column for any amount of time, you may have noticed that I’m a big fan of using code to test code. This includes automated tests of all kinds - unit tests, behavioral test, functional tests, etc. This means that whenever possible if there’s a bug reported, I’ll try to write a unit test or Behat test that expects the correct behavior. This test will fail, and then I’ll create the fix for the bug. The test and the fix will be submitted together which then ensures that going forward, that particular bug will not happen again. If it does, the automated builds will catch it and prevent the regression from being deployed.

A quick example of how this might work. In an API you may be passing the ID of a resource via the URL. This ID will be involved in a SQL query to fetch the data for the resource. Suppose the ID field in the database is defined as an integer or similar. With Postgres, and possibly other databases, trying to add a “where” clause on an integer field that compares to a string will give back a SQL error along the lines of “banana is not an acceptable representation of an integer”. This means that I need to be sure that I’m only requesting integers from the field. (Please note, this happens even with prepared statements, I’m not just blindly passing everything to the database). The Behat test I would write would make a request to the API but passing in a non-numeric string ID. I’d then add expectations that a specific error would happen - perhaps a 404 indicating that the URL doesn’t represent a resource, or a more specific type or error that shows the ID must be numeric. That test will fail when the SQL error happens, but should pass once the validation of the ID is in place. With the combination of the test and the bug fix, we can be assured that this bug is gone.

I also encourage my QA team to build Behat tests when they find bugs. This allows them to enter bug reports with actionable, runnable tests that I can use to help find the problem. Additionally, the validation step that they’d normally need to to to ensure the bug was properly fixed is no longer needed. Once the bug is fixed, the tests pass and the QA team can rest easy knowing that the bug is gone and is not coming back.

Conclusion

Bug reports that are valuable help developers find and fix the bugs quickly. These reports need to have reproduction steps as well as actual and expected outcomes. By clearly communicating these expectations in the form of a well-written bug report, or making sure the people who are reporting bugs know what is needed, we can help reduce the time it takes to find and fix bugs. Properly categorizing the priority and severity of bugs let developers know what to spend their time on next to improve that application. By fixing code via TDD or by including automated tests along with the bug fix, developers can help ensure that regressions are minimized and prevented and QA can be assured that the bugs they reported have been properly fixed without needing to resort to manual verification of bug fixes. Finally, by treating bugs as something to eradicate quickly after they are found, you help ensure that your application works as well as it can and will be maintainable for a long time to come.